On Dumb Questions

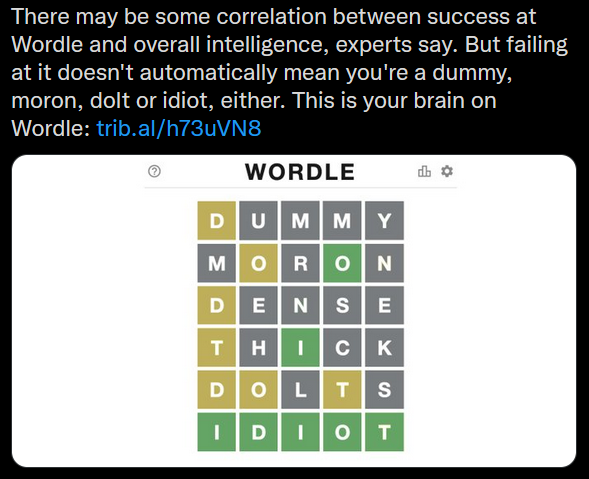

Sometimes the internet is simple, someone can post something that is upsetting and so you get upset. It’s linear and easy. Yesterday, the internet gave me something that just made me stir. Stir is a fun word for it, because it felt like one feeling with a million different ingredients in it. Here is that thing:

This tweet was attached to a twitter moment, whose headline was “Being Bad At Wordle Doesn’t Mean You Are Dumb. Here’s Why.” These words hit my brain very awkwardly. Despite knowing she is just saying “I feel dumb when I do bad”, the point at which my internal soup starts bubbling is at “So I went to an expert to find out.” Those experts were two psychology professors, a postgrad in cognitive sciences, and the highest titled person working at Lumosity. The reason I start to stir is not because I’m disrespectful of these experts, besides the Lumosity guy, but because this feels like absolute overkill. There is a cadence to new school journalism ripped straight from late night NPR present here “Here is my silly life thing, let’s solve it with science.” Now, I love a good fuck-around-and-find-out. The problem here is, as every good scientist knows, that your find-out is only as good as your fucking-around, and to fuck-around well means asking good questions. So let’s talk about dumb questions.

~~~

While the flavor of the joke above is “look at how impressive I am”, the reality is that today’s puzzle brewed an existential disappointment within me. An eye opening revelation about how perspectives shape our realities in the world. A true sad clown moment. When one is faced with the threat of not completing a puzzle, while all their internet friends seem to have an easy time with it, the perspective shifts to not finishing. So imagine you are a small body standing next to a giant Wordle board. Below you is the hell of living a life aware of your own incompetency. On ground floor 6/6 are the people that have narrowly escaped that doom. Floors 4 and 5 are purgatory where the plebs live. Floors 3 and above are inconceivable and fairly far from your view. You just see flashing green and yellow lights, and imagine that’s where the chosen ones reside.

I’m on my 11th Wordle and currently averaging a 3.9, above a what was proclaimed “a gentleman’s score” by the tweet which introduced me to the puzzle. Today my first word was [S]C(O)UT. I’m coming off a short Wheel of Fortune kick, so I think “RSTLNE” and guess [S][O][L][A][R]. I’ve made it. Round two! My big break! I’ll be bumping elbows with the elites in no time. Just a few days earlier I found myself narrowly escaping a life of public ridicule as my turn 3 guess of [T][A]FF[Y] was followed by [T][A]BB[Y], [T][A]LL[Y], and then finally [T][A][N][G][Y]. As I went to post my 2/6, I felt a sinking feeling of unearned accomplishment. “When I post this,” I thought to myself, “I will be the champion of little people. There will be parades in my honor… and yet, it was simply a guess. ):”

If we take the perspective of a Wordle board from the top down, we’ll notice that it can’t possibly be so linear as the bottom up view. If getting it in 2/6 is mostly luck and 1/6 is obviously luck, what glory is there in a high score? How can we view any further stages of completion as anything other than starting from an initial lucky guess?

~~~

The journalist behind the Wordle article is approaching it in the same way that she approaches the puzzle. “I am but small. Let us look to those on the mountain.” She climbs that mountain, seeks council with the wise ones, and returns with only “The evidence is inconclusive to whether I am dumb or not.” It reads quite literally like a zen parable, and with the same punchline of her big question being met with a underwhelming response and her initial premise being the culprit in that.

The reason that these experts may not have been the right people to approach for the question of “Am I Dumb?” is shown by their not unanswering of her question. That may be because “dumb” is not really an academic concept (at least not explicitly) in all but the dark nazi corners of neuroscience. An interesting thing in the article is that most of the answers given by the experts are not necessarily scientific statements, but logical statements of an objective flavor. For example, she talks with a psychology professor about how one could step away from a Wordle puzzle and come back to it with fresh eyes. Sure, that is a process of the brain, but do we just ascribe all questions of the brain to those who study it? The history of neuroscience shows it to be one of the most drastically shifting fields in academia as well as the one with the most left to discover, perhaps behind (or in a superposition beside) theoretical physics. After all, the author is a writer! Surely the mental process of leaving and returning to a project is more in her wheelhouse than a psychologist.

So what that would be the right question to approach the neuroscientists with? Simply, one where objective truth is what we are looking for. Why this light-hearted article with liberal sensibilities is really getting under my skin is because the premise inherent in this bad question is that “dumb” is something we can test for. I like to think the author knew the answer would be bigger than her question, but I still find myself dissatisfied with the end points the article lands on. So, allow me to try my hand at this as a non-expert of really much of anything at all.

~~~

Better questions to ask than “Is my struggling with Wordle proof that I am dumb?” would be “What are the components of Wordle that cause me to struggle?” and then “Why do I struggle with those components?”. Identifying components is an interobjective exercise where one looks at mechanisms of systems. Let’s call that ‘game design’. Reasons for one struggling with something exist as a combination the objective and the subjective, made up of both the capacity of any human body and the contents of an individual’s starting state. Let’s call that mixture ‘performance’. They are clumsy terms but they will take us where we are trying to go.

The article does a fine job of showing how the puzzle is a bit of a bait-and-switch, displaying letters to train your brain into thinking linguistically when really it’s a spatial recognition exercise, much like “4 is the magic number”. However, Wordle is actually much simpler than the neuroscientists articulate it. Each puzzle is really just about narrowing possibilities. There are 158,390 five letter words in the English language (perhaps more because the maker is British [ABBEY my ass]) and you have six guesses to narrow it down to one word and then find it. So in theory, optimizing for this game means finding the word which uses the most popular letters in order to bring the 158,390 down as low as possible. In practice, however, the fact that the game designer is quite likely deciding the word each day means that words with tricky letters may actually be more likely than they’d be in a random set. For that reason, I can now stop calling this a puzzle and we can start thinking of it as a game with two players. It’s a somewhat informal game, but arguably a game nonetheless.

The game can be broken up into a beginning, middle, and end phase. The beginning phase is when we start with no special information, only that the answer will be a five letter word: A blank board. The middle phase is when we have any extra information at all, but the word has not taken shape yet. The end phase is filling in the gaps once we have the basic structure of the word. Outside of data mining or a python program, each phase has its own unique skill that one might lean on for solving the puzzle. The beginning phase interacts with one’s ability to craft words with specific letters, assuming one knows the most used letters to begin with. The middle phase has the solver putting available letters in their most likely places, a similar skill to the previous phase yet also involves anticipation and thinking ahead. The end phase is the point of a hard shift to prioritizing spatial intelligence, which is in itself a unique intelligence for one to develop and where some may struggle with the game.

Yet, however undeveloped we find spatial intelligence to be in the average human, I’m fairly certain we’d find performance to be even much less developed. This is because performance is made up of a variety of factors which are not often prioritized in childhood development including managing energy, mindfulness, self-awareness, self-trust, and perspective taking. I found Wordle in the first day of a 10 day quarantine with my partner. Every day I’d do my own Wordle first and then get to watch them do theirs. I remember a puzzle I magically got in three: LO(U)S(E), A[U]G(E)(R), [Q][U][E][R][Y]. While watching them do their puzzle they had somehow selected every common letter that wasn’t in the word and had just an (R) and I was convinced I’d be just as stumped if I was in that spot. On a tough day when someone is sick or overtired, that situation could make you feel anywhere within a range of annoyed to not a real human. Couple that with the quite common condition of test taking anxiety and it could drive you pretty mad.

Combine that with the social perspective of viewing the game from the bottom up and this, to me, is the essence of why one might ask “Am I dumb?” when struggling with a puzzle. Completing this simple word game is made up of many components that if you took the time to dig, could actually make it exhausting. That’s likely a point for the casual gaming team. Although, games can be thought of as exercises for dissecting complex systems. When you start to break those systems down to components, you start to see those components in the complex systems between you and your loved ones or you and the forces which govern you. Point one for the nerds. The first step is the beginning phase. Ask good questions. Use good starting words.

I want to end with an interview I saw the other day with James Carse. Carse wrote Finite and Infinite Games, which is really just the most enlightening book on philosophizing about games and life. I’m not invoking him for that reason though. He’s done a bit of writing on religion though, which I haven’t read, but in this interview he talks about science and belief systems in a way which somewhat enlightens this problem I’m recognizing with how the author of this article appeals to science.